Why What We Don’t Say Matters Most

There are moments in life when something lingers just beneath the surface. It may be an image from a dream, a flicker of emotion, or a thought that feels too strange or shameful to name. These unspoken moments often hold the greatest power in therapy, and understanding or speaking to them, can perhaps shed light on how we begin to heal.

In the writings of Nietzsche’s Twilight of the Idols, he famously wrote: “Silence is worse; all truths that are kept silent become poisonous.” In a similar tone, Freud, decades earlier, offered a guiding principle for psychoanalysis: “The patient must relate everything that comes into his mind… even if it is unpleasant to tell.”

These two ideas, seemingly from different corners of thought, converge on a simple but profound truth: what is unspoken holds weight. And on the therapy couch, it can be the key to a sort of traversal.

The Struggle to Speak

When people come to therapy, they often believe they must already know what to say. But more often, something different is discovered when there is an allowance to speak to something not planned or pre-scribed. Some find it hard to recall dreams, not because they forgot them, but because saying them aloud stirs an unconscious desire they fear to confront. Others hesitate to speak obsessive thoughts aloud because the content feels “strange” or shameful, even though these thoughts may dominate their daily lives.

This resistance isn’t just avoidance; it’s a meaningful signal from the unconscious. Psychoanalytically, resistance is a kind of compass and it points toward something unresolved, hidden, or repressed. It is often the threshold where the most profound therapeutic work begins. Rather than being an obstacle, resistance invites exploration. The unspeakable isn’t a void rather it is densely packed with affect, memory, desire, and meaning. Often, it guards the very material that has shaped a person’s internal life just waiting to be encountered and symbolised through speech.

Speech as Transversal

Therapy is not always about quick insights or polished strategies. More fundamentally, it’s about making space for what resists being said. The process of speaking itself can be powerful. Trying to give form to what was previously formless often becomes a turning point.

Many are surprised by the relief they feel after voicing a painful memory or naming a desire for the first time. The act of speaking, even when halting or incomplete, initiates change. It makes room for meaning, for interpretation, and for relief.

As Freud famously responded to a patient who resisted saying a difficult thought, “You might as well ask me to move the moon from its orbit.”

This resistance is not a failure. It signals that something important is beginning to emerge.

Why Speaking Matters

Speaking allows the unconscious to become, in some small way, conscious or that is, signified. It allows the psyche to symbolise experience rather than remain stuck in repetition. The process is not always cathartic, but it is always revealing.

Think of it like this: language acts as a bridge between what we know and what we have yet to understand. When we speak, we do more than describe our experience – we shape it. We begin to see patterns, contradictions, and underlying meanings that were previously obscured.

This is especially true in psychoanalytic therapy, which isn’t about solving problems in a linear fashion but about listening differently. Listening for the moments of hesitation, the subtle pauses, the unintended slips that reveal more than intended. These are the moments where meaning leaks out.

We Are All Divided

One of the most grounding and humanising ideas from psychoanalysis is the recognition that we are all composed of contrasting parts: conscious and unconscious, rational and irrational, aware and unaware. Divided subjects. We carry within us layers of experience, desire, and memory that are not always available to us. We all have aspects of ourselves we don’t fully know, and at times, cannot bear to know.

But that’s not a flaw. That’s what makes us human. It means we are complex, evolving, and always in the process of becoming.

So, when someone walks into a therapy room and hesitates, when their voice shakes or they pause mid-sentence, unsure whether to continue, I see immense courage. To speak honestly in the face of shame or fear is no small feat. It’s an act of vulnerability and strength at once.

This struggle to speak, to give shape to what was buried, isn’t something to overcome quickly. It is the work of therapy. It is where the real transformation happens.

We are not searching for the perfect way to express ourselves. We are seeking truth in its raw, imperfect form. The act of moving from silence into speech, of glimpsing something previously unknown within ourselves, even if just momentarily, is an achievement that deserves to be honoured.

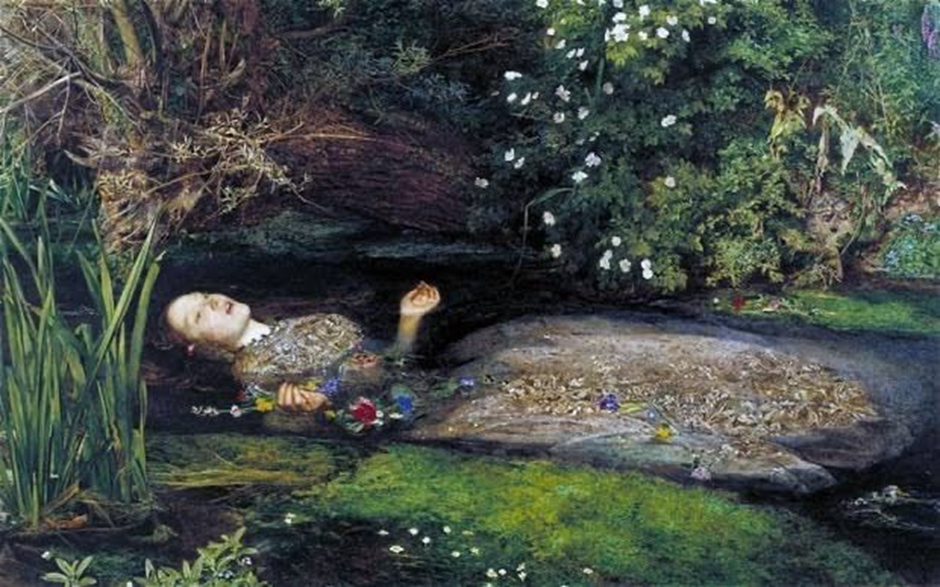

Ophelia and the Silence of Desire

To conclude, I want to return to the image that inspired this reflection: Ophelia by John Everett Millais. In Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Ophelia becomes a tragic figure of unspoken longing and suppressed voice. Her descent into madness and her death symbolise the cost of what is left unsaid.

In our world, unspoken truths may not always lead to tragedy, but they often manifest in symptoms: anxiety, compulsions, somatic pain, or deep sadness. Speaking, then, is not just a therapeutic tool. It is an act of reclaiming agency, of allowing the unsayable to be heard.

In therapy, we hold space for this difficult speech. We listen with care. And sometimes, simply putting something into words is what begins the healing.

So if you find yourself hesitating, circling around something, unsure if it’s worth saying – know this: it is.

Often, the thing hardest to say is the very thing that needs to be heard.

If you’re looking to begin a deeper work or simply want to speak, please get in touch

Myles Medwell is a clinical psychologist in Melbourne who works with adults and young adults through psychoanalytic and depth-oriented approaches.